This article is part of the Signals over Noise newsletter also accessible on LinkedIn.

Ask someone how much they'd pay for a pizza that stays fresh in the fridge for a year and magically grows back to its original shape after each slice—and they'll give you a number. Maybe $20. Maybe $100. Some will confidently say $500. The answer is meaningless because the product is too abstract and they have no ability to gauge the pros and cons. But you'll get data. This is an absurd example, but it illustrates the limitations of traditional surveys—limitations that some consulting companies seem to ignore, especially when it comes to connected cars.

The Disconnect: What Surveys Miss

For years, consulting firms predicted connected car services would become a major revenue stream for OEMs through subscription models. The reality has been far more muted. Most firms have quietly walked back their projections, acknowledging that connected car revenues have underperformed and that much of the value has been bundled as standard features rather than premium add-ons.

However, Deloitte's 2026 Global Automotive Consumer Study strikes a notably different, more enthusiastic tone—and serves as a useful case study in how careful we need to be with surveys as they can produce misleading conclusions. I'll focus on three data points from Southeast Asia that illustrate these problems.

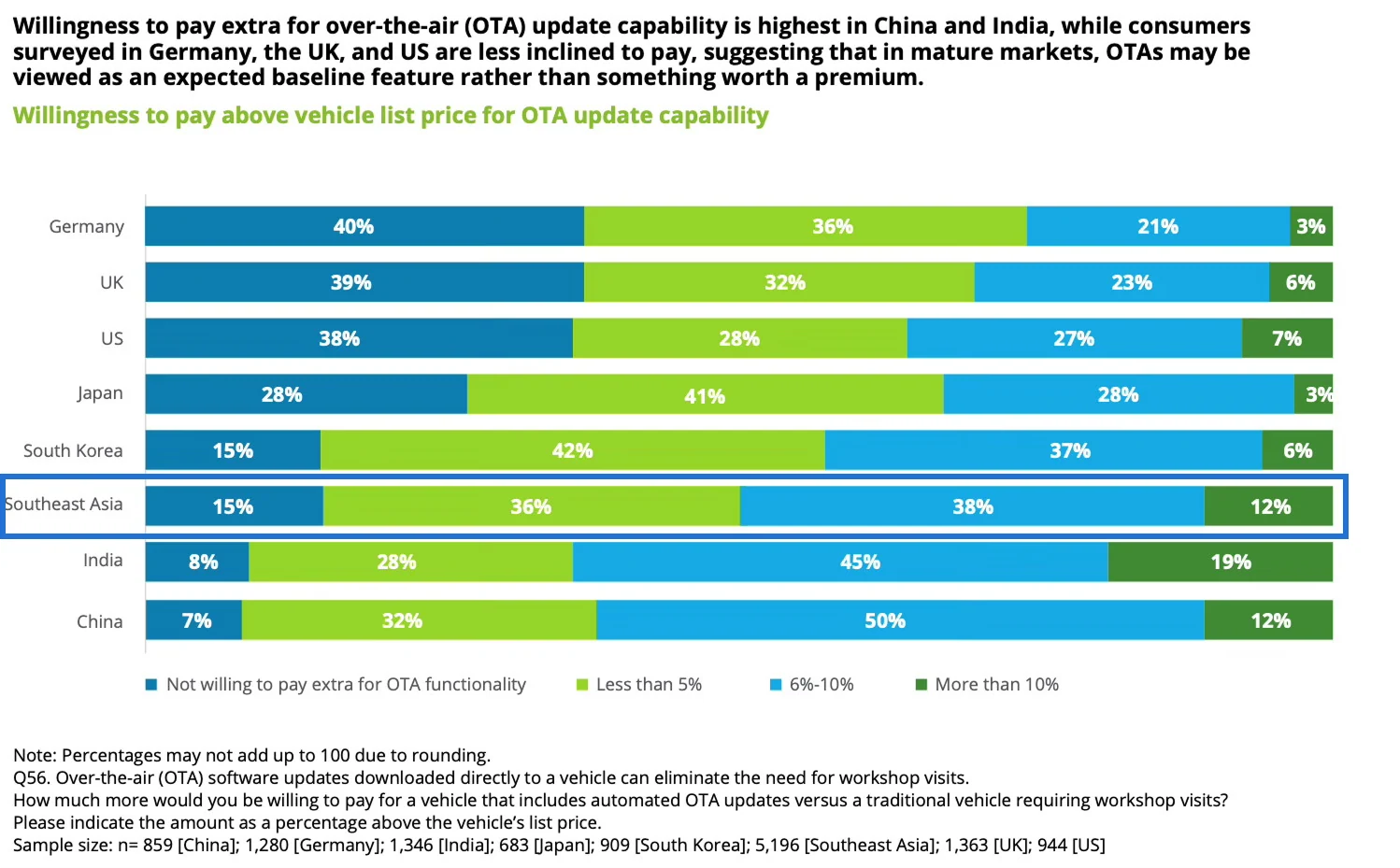

Data point #1: 85% of respondents are willing to pay extra for Over-the-Air (OTA) update capability, with the majority willing to pay 6% or more above the vehicle's list price.

There are two significant problems here. First, willingness-to-pay questions are notoriously unreliable. This is one of the most common areas where you'll observe a large "say vs. do" gap—people consistently overestimate what they'll actually pay compared to their real purchasing behavior. Most of those who have tried launching a revenue-generating service based on survey feedback like this have likely learned this lesson the hard way. I generally advise skipping willingness-to-pay questions in surveys entirely.

Second, Deloitte's definition of OTA is misleading and undermines the entire question. The survey asks: "Over-the-Air (OTA) software updates downloaded directly to a vehicle can eliminate the need for workshop visits. How much more would you be willing to pay for a vehicle that includes automated OTA updates versus a traditional vehicle requiring workshop visits?"

This phrasing creates critical ambiguity. Respondents could reasonably interpret this as either: (a) updates can be done remotely instead of visiting a service shop for software changes, or (b) OTA capability eliminates the need for all workshop visits. Some respondents may believe they're paying for a vehicle that rarely needs service at all, when in reality they're only paying for remote software updates that reduce software-related visits. The car still needs oil changes, brake service, tire rotations, and all the physical maintenance that actually consumes time and money.

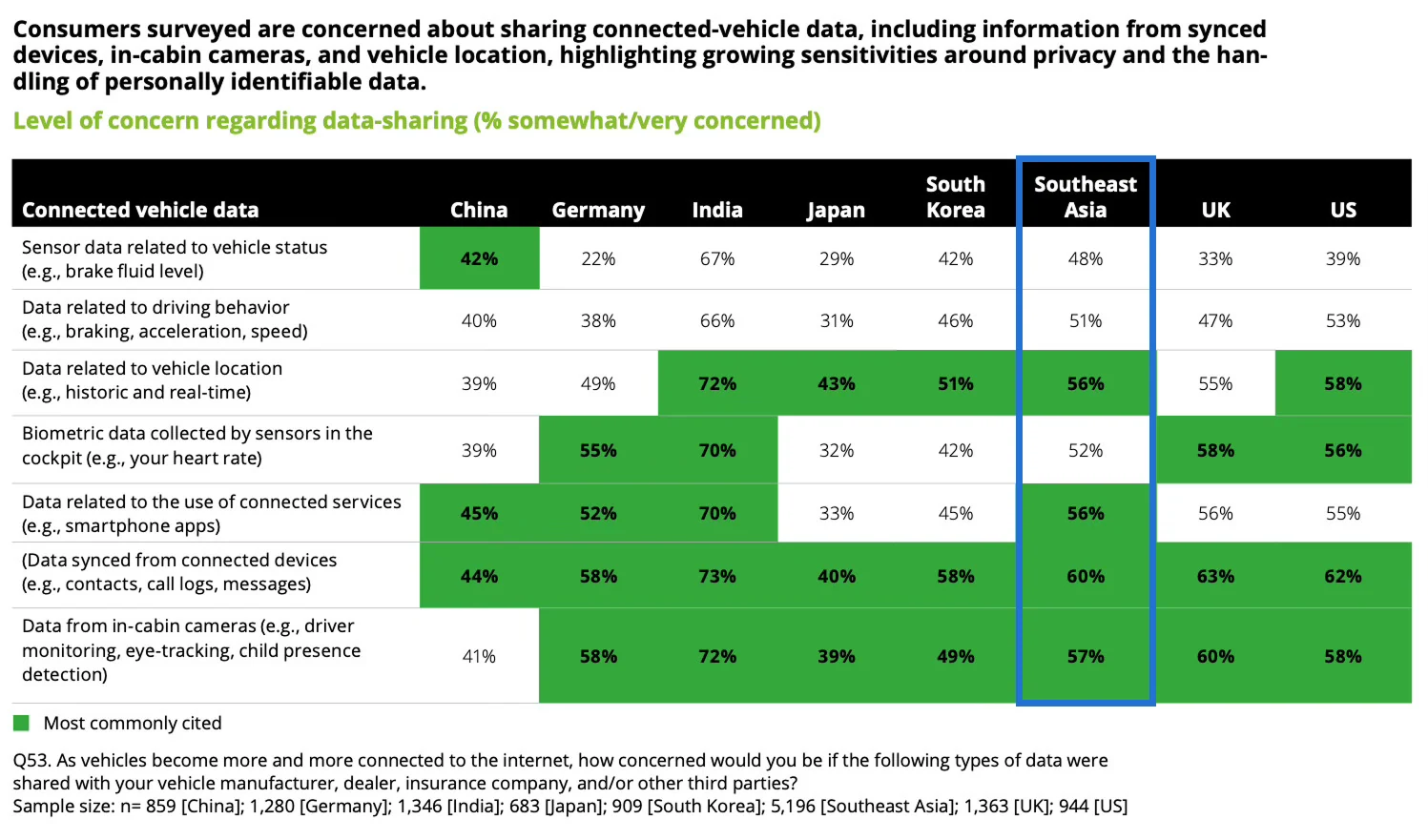

Data point #2: Most respondents are concerned about data-sharing, with communication data from phones, data from in-cabin cameras, data from smartphone apps, and data related to vehicle location ranking highest among respondents (with 56-60% being somewhat or very concerned).

The question itself was flawed. Deloitte asked: "As vehicles become more and more connected to the internet, how concerned would you be if the following types of data were shared with your vehicle manufacturer, dealer, insurance company, and/or other third parties?"

This bundles wildly different entities—manufacturers (recalls, improvement), insurance companies (pricing), and vague "third parties" (advertisers? data brokers?)—into a single question. Respondents likely have different comfort levels for each, but are forced to give one answer. The question also provides no context about purpose: safety improvements? Targeted ads? Sold to brokers?

In addition, the focus on data sharing appears misaligned with actual customer pain points. While data sharing concerns are legitimate from a regulatory and brand-risk perspective, they are rarely what determines whether a customer loves, hates or is very concerned about when it comes to their car. Based on our Auteneo dataset of real customer interactions, such discussions are rare. When customers discuss connected cars, they're far more concerned with practical issues the survey did not ask about such as:

- Vehicle not remembering software settings after updates

- Persistent connectivity issues and poor network signal

- Unstable software and frequent freezes

- Difficulty pairing phones with infotainment systems

- Features suddenly disappearing after updates

- Wishing some new features were available

When privacy topics do appear, they're more often technical frustrations: "Privacy policy pop-ups won't stop appearing every time I start the car—how do I fix this?" These are support requests, not philosophical concerns about surveillance.

Even location privacy discussions tend to be lighthearted. When Tesla introduced a feature to hide vehicle location from other authorized drivers, the response was humorous rather than earnest: "Turn this off = immediate interrogation from spouse" and "Too late—now she knows tracking was possible." Tesla solved a technical problem while highlighting a social one—nuance that would be difficult to imagine without deeper customer understanding first.

The overall pattern here is the following: data sharing concerns get treated as strategically crucial—worth detailed measurement, executive attention, and research investment—while actual user experience may not get enough attention it deserves.

Data-sharing concerns are not illegitimate, but they are hygiene factors. Their presence does not create value; their absence destroys trust. The primary question is whether users actually want to use the product at all—whether it works reliably, feels intuitive, and does not frustrate them during basic tasks.

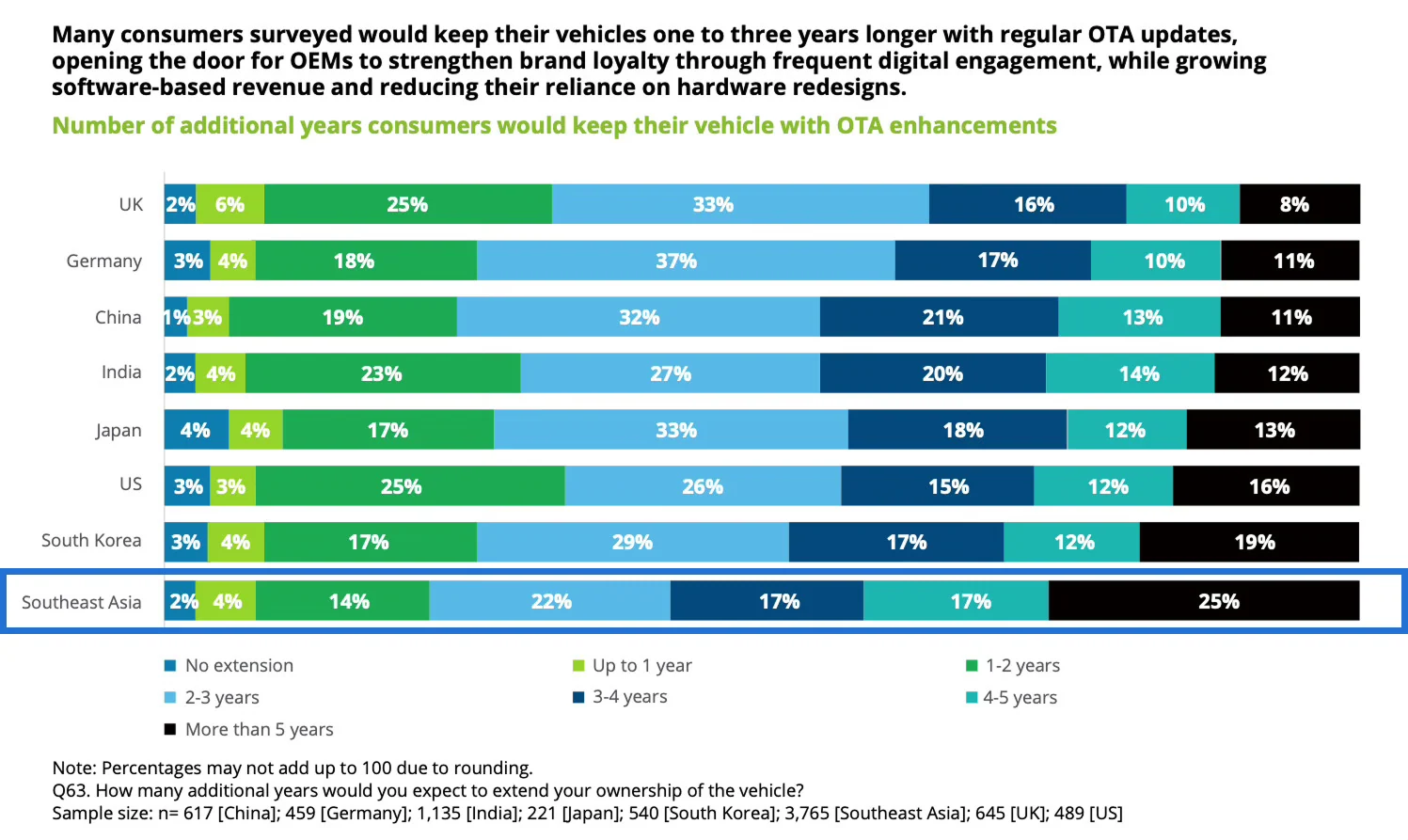

Data point #3: 98% of respondents would own their vehicle longer if it had regular OTA updates with 25% of respondents claiming that feature would increase the ownership length by more than 5 years.

The survey asked: "How many additional years would you expect to extend your ownership of the vehicle?"

This question suffers from multiple problems. First, it asks people to predict future behavior based on a feature many haven't experienced—another classic "say vs. do" gap. Second, it assumes OTA updates would be the determining factor in ownership duration, when this decision actually depends on far more critical factors: finances, mechanical reliability, repair costs, and changing family needs. Related to that, asking someone to predict their car ownership decisions 5+ years out (not an uncommon car ownership time period) is asking them to forecast across potential recessions, job changes, family expansions, and technology shifts they can't possibly anticipate. It's the self-regenerating pizza scenario all over again: indicating behavior related to something impossible to genuinely imagine.

Reconnecting: Stop Asking the Wrong Questions

Surveys remain useful tools, but we need realistic expectations about what they can and cannot tell us.

- For high "say vs. do" gap risk questions, stop surveying entirely. Willingness-to-pay data from surveys is fiction. Instead, test with experiments that measure actual behavior: add "coming soon" features to your mobile app and track click-through rates, A/B test different price points on mock configurator pages, offer early access reservations that require payment commitment, analyze conversion rates from similar features in the market, or build app-only prototypes that simulate the experience and measure free-to-paid conversion. These approaches are worth considering even before full development—fake door tests and waitlist signups with pricing cost little but can reveal infinitely more than asking customers about something they've never experienced.

- Start with organic discussions, not survey design. The most common failure is surveying the wrong things entirely. Before designing questions and answers, analyze what customers actually openly discuss: on forums, social media, support tickets. This will reveal your blindspots and help you probe into topics that really matter. Listen first, ask later.

- Question and answer framing matters enormously, but traditional surveys are trapped in a static format that can't adapt to individual respondents. If someone misunderstands a question, there's no way to clarify. If their answer suggests they need a follow-up, the survey can't ask it. AI could fundamentally change this—enabling conversational interviews that probe when responses seem confused, clarify ambiguous questions in real-time, and follow promising threads that a static form would miss. This is still an emerging area with early-stage developments, but it's worth monitoring as the technology matures and could eventually reshape how we gather consumer insights.

This matters especially for connected cars and software-defined vehicles, where the product is increasingly digital. The hardware-era playbook—long development cycles, infrequent customer feedback, survey-driven insights—doesn't work for software that updates continuously and generates behavioral data in real-time. Digital products require digital-era research: observing what customers actually do, measuring which features get used or ignored, and understanding pain points through support patterns and organic discussions, not hypothetical predictions.

At Auteneo, we believe some things are fine as they are (Italian food), while others desperately need improvement (automotive market research). Do you agree?